Banning Lead For Outdoor Sporting

| HOME |

| LEGISLATION |

The Danger's of Lead Tackle and Shot

Lead Tackle

For years, fisherman have used lead sinkers and lead-head jigs (weighted hooks) as an easy and effective tool because they are cheap, heavy and easy to mold to a fishing line with pliers because of their ductility. Open most any tackle box, or shop at a local bait store, and there is a high probability to find lead sinkers and jigs to be the only kind available (Figure 1). Lead sinkers and jigs generally weigh between 0.5 and 15 grams, range from 0.5 to 10 centimeters long (Sidor 2004).

Figure 1. Lead sinkers ranging from 0.5 to 15 grams (Hudolin 2004).

Lead sinkers and jigs are frequently lost when:

-

They are caught on snags from vegetation or rocks that lay on the floor of a lake, pond, or stream.

-

The line becomes so entangled that the line breaks or is cut.

-

Also, because they are so tiny (size of a BB) they are often mishandled by anglers and are dropped along the shoreline,

-

Or are simply discarded into the environment because they have become ‘pinched’ and cannot be attached to the fishing line. These weights have been unconsciously disregarded because of easy availability, cheap cost and a lack of education to the growing problems of indirectly harming some species of waterfowl and increasing lead concentrations in our waterways.

The ingestion of a single sinker or jig can be lethal to many different species of waterfowl . Lead poisoning due to fishing tackle has been documented in 25 species of birds and in sensitive species including Common Loons (Gavia immer), Trumpeter Swans, Mississippi Sandhill Cranes (Grus canadensis), and Bald Eagles (see Figure 2). In New England, poisoning from lead weights and jigs is the greatest source for loon mortality, accounting for 50% of adult deaths (Sidor 2004). Likewise, in Canada, 30% of adult loon mortality is due to lead poisoning resulting from sinker ingestion (Scheuhammer 1995).

Figure 2. Bird Species poisoned by lead fishing tackle (USFWS 1994).

| Sensitive Species | Common Loon, Trumpeter Swan, Bald Eagle, Mississippi Sandhill Crane |

| Waterfowl | Canada Goose, Mallard, American Black Duck, Ring-necked Duck, Redhead, Wood Duck, Common Merganser, White-winged Scoter |

| Wading Birds | Sandhill Crane, Great Blue Heron, Common Egret, Snowy Egret, White Ibis, King Rail, Clapper Rail |

| Gulls | Herring Gull, Laughing Gull, Royal Tern |

| Pelicans | Brown Pelican, American White Pelican, Double-crested Cormorant |

Lead Shot

In 1991, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service banned lead shot for waterfowl hunting to minimize lead exposure in both waterfowl and Bald Eagles (USFWS 1994). Although, this ammunition is still acceptable for upland hunters and is likely to be deposited into many wetland areas. This has created an immeasurable amount of lead remaining in wetlands throughout the country. A number of water birds, exhibiting different feeding strategies, are exposed to such lead (Bellrose 1959). A single lead pellet is enough to produce lethal poisoning.

There are many different niches of waterfowl that could potentially be exposed to deposited lead, which range from bottom feeders that dig deep into the mud to shoreline feeders. Thus, the combination of old spent shot and newly deposited spent shot can have lethal effects on many types of waterfowl. Also, soil conditions can play a significant role in how deep the lead penetrates. Pellets that sink deep into soft sediments (sand) would be less likely to be ingested when compared to those that come in contact with hard sediments (clay).

There is a threat to upland bird species, too. Many of these birds feed on the grains and seeds located near fields. Spent shot pellets closely resemble these favored foods. Many small game hunters are attracted to these areas each fall because of the ideal feeding areas for attractive game species. This leads to increased lead deposition in these areas and therefore increases the threat of lead poisoning for many different bird species.

There is a strong possibility that lead deposition from trap and skeet shooting could negatively impact the environment and could cause lethal poisoning to many different bird species. If the shooting is occurring near a waterway, it is strongly recommended that the club use alternative shot types or stop shooting altogether. High levels of lead can be detected easily near waterways because plants uptake lead from contaminated sediments.

-

Currently, the EPA is cleaning up 32 properties in the Lexington Manor subdivision in Liberty Township, Ohio (The Journal-News 2004). This site was a skeet shooting range, which closed in 1969. The plan calls for the removal of 25,000 tons of soil from the 22-acre development, ranging in depth of one to five feet, depending on the degree of contamination (The Journal-News 2004).

Lead Poisoning to Birds

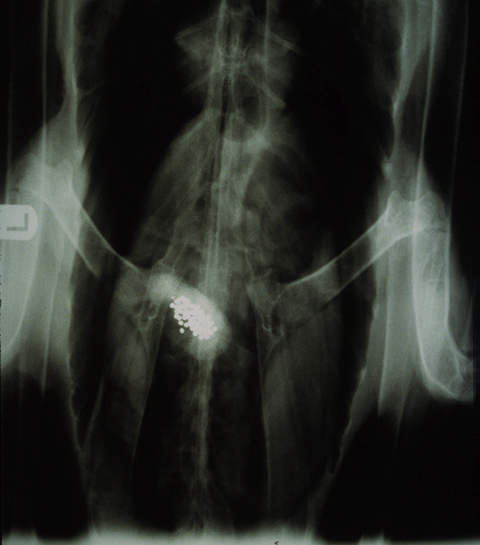

Among the species of waterfowl, ingestion of lead fishing tackle (see Figure 3) or shot during feeding, when they either mistake the sinkers and jigs as food items, small rocks (grit) needed to aid in digestion, or consume lost bait fish with the line and weight still attached (Sidor 2004). Predators, such as the Bald Eagle and Osprey, that take fish containing tackle are susceptible to secondary lead poisoning (ingesting prey that has been effected by lead poisoning) (USFWS 1994).

Figure 3. Lead in the gizzard of a Trumpeter Swan (Hudolin 2004)

Once ingested, the lead is broken down by digestive acids and grit, along with other food items, and is distributed throughout the bloodstream. Depending on the amount of lead ingested, the waterfowl may die within two days or as much as two weeks, or suffer ill effects from low levels of lead toxicity. Some of the signs of lead poisoning include listlessness, emaciation, and loss of balance (Sidor 2004). Once poisoned, a sick bird will be weakened to a point where it can no longer feed or perform other functions needed for survival, such as walking or flying to escape predators, which may result in death.

Common Loon Research

The Common Loon (Gavia immer) has been a symbol of wilderness for many years for residents of the northeast United States and eastern Canada (see Figure 4). It has attracted similar kinds of public following and public attention that was once reserved for more typical population sensitive species like bald eagles and gray wolves. They have been proposed as indicators of aquatic health in the northern lake ecosystems they inhabit (Scheuhammer 1995).

Figure 4. The Common Loon (Weber 2004)

The effects of lead sinkers and jigs on waterfowl is well-known, but the total number of mortalities is less understood because poisoned birds usually hide in dense cover or are eaten by predators. Also, the Common Loon is illusive by nature, which increases the difficulty of monitoring. While the full impact of lead poisoning on wildlife is not known, further studies may reveal that lead fishing gear may be a bigger problem that some might have expected.

In 1992, Dr. Mark Pokras of Tufts University published a paper showing that 52% of the dead loons (16 of 31 adult birds) that he examined from New England, starting in 1987, died from lead poisoning due to the ingestion of lead sinkers (Sidor 2004). In 2000, the report was updated to include more loons collected, showing 44% of the dead adults (111 of 254) died from lead tackle ingestion (Sidor 2004). The common types of lead tackle recovered from these loons where sinkers and jigs (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Lead Types in Loons (Sidor 2004).

There is currently insufficient evidence that shows whether or not lead sinker poisoning is effecting population dynamics of the Common Loon in the Northeast U.S. or in Canada (see Figure 6). Population estimates can be made by using individually marked waterfowl to obtain population parameters in a given region. The information collected can then be analyzed by using software such as geographical information systems. To conduct a larger-scale study of Loons would be very expensive and time consuming. It would require long-term monitoring of a significant number of banded individuals.

Figure 6. Low Populations (Sidor 2004).

It is understood that lead sinkers, alone, do not pose a threat to completely wipe out loons, but it is a contributing factor that is manageable. There are other ways loons populations can be disrupted, they are:

-

Acid rain kills off fish (main source of feeding).

-

Large waves from jet-ski's and motorboats can destroy nesting areas.

-

Mercury pollution can interfere with breeding.

Lead Shot Research

In the late 1930s and 1940s, thousands of ducks and geese were dying off in the Mississippi Flyway due to lead poisoning. Research conducted by Bellrose (1959) was conducted to determine the extent of the problem.

-

His survey revealed that, in fact, ducks and geese were especially susceptible to lead poisoning and that most die-offs occurred after the hunting season in late fall and early winter (Bellrose 1959).

-

He estimated that over 100,000 lead pellets per acre could accumulate by the end of the hunting season and ingestion was due to mistaking the pellets for food or grit (Bellrose 1959).

-

This research has been the foundation for many studies conducted today and was the leading cause for the passage of the 1991 ban on the use of lead shot in waterfowl hunting.

Lead Deposition and Transfer

Lead is commonly recognized as a poisonous and has been removed from use in gasoline and paint. Until recent years, lead sinkers, jigs and shot have been thought to be harmless to the environment but obviously damaging to some bird species. Lead contamination and transfer was always thought to be impossible because of the size of a single sinker or jig. Although, if you dump something into the environment, it doesn't just go away. It will show up again some other time, or some other place.

Each year in the United States, lead sinkers make up 50% of the sinker market; total estimated weight is over 2,700 tons (USEPA 1994). The full extent of sinker loss and deposition into the environment is unknown because it has not been fully researched. Although, it is expected that accidental sinker loss can result in a substantial amount of lead deposition in wetland environments where fishing is popular.

It is estimated that 500 tons of lead is deposited into Canada's waterways each year (Scheuhammer 1995). That is essentially the equivalent weight of dropping 500 cars into our lakes, rivers and streams each year. Over time, this continual increase in lead deposition will be transformed into particulate and molecular lead species and will be dispersed through the environment to some degree (Scheuhammer 1995).

When it decomposes in the environment, which can take decades, lead can contaminate soil and water and create negative impacts to aquatic species and humans. Lead may leach into soils or sediments and be transferred to aquatic invertebrates within the sediments, thus leading to the dispersal to higher trophic levels, which will create a much larger problem for many species – not just birds.

Contaminated drinking water from lead ions can cause serious health problems to humans, such as hypertension, miscarriage, and childhood brain damage (Scheuhammer 1995). This can be caused by the lead ions that leach into groundwater from contaminated sources and can eventually reach drinking water.

| BACK TO JSC STUDENT PAGES |

| MY RESUME |

| EMAIL ME |