|

|

The Georges Bank is located in the Gulf of Maine. It is an elevated part of the continental shelf that stretches under the ocean from Massachusetts to Nova Scotia. At approximately 240 kilometers long and 120 kilometers wide, it is about the size of the state of Massachusetts (See Figure 1). Historically known as prime feeding and breeding grounds for herring, cod, haddock, and scallops as well as many other shellfish, fish, mammal, and bird species, it was once one of the world's most valuable fishing grounds.

|

|

Figure 1. Map of Georges Bank (CLF 2004)

The

Georges Bank was once part of the mainland, but as the climate warmed, ice

melted from the thick ice sheets covering North America, and consequently

sea level rose. Georges Bank went from being part of the mainland to

becoming an island about 11,500 years ago (AMNH

1998). During its time as Georges Island, its

climate was suitable for vegetation and was inhabited by an array of

wildlife including walruses, mammoths, mastodons, giant moose, musk ox, giant

sloth, tapir, and even man. Evidence of its terrestrial history is still

occasionally dredged from the Bank’s floor (Amaral

1999). As warming persisted and the sea level continued to rise,

Georges Island was eventually flooded about 6,000 years ago

(NPS

2005). To see this progression animated, please click

here. Glacial activity

has also provided the Georges Bank with the diversified sediments that provide the

necessary habitat for many

marine organisms. Glacial deposits of gravel pavement provide needed for scallops to colonize,

as they can not attatch to shifting sands and is

perfect for spawning fish, while the coarser grains provide hiding places for

juvenile fish and the small creatures they prey on (Valentine

2003).

The Georges Bank was named by English colonists in 1605 (Amaral 1999), but was already legendary. The Basques first discovered Georges Bank around 1000AD, and tried to keep the bountiful fishery a secret, but it wasn’t long before Basque fishing fleets were spotted anchored above the Georges Bank (AMNH 1998). News traveled fast, and soon the worldwide fleets were exploiting the fishery. At that time no one could imagine exhausting the fishery because fish were so abundant the water would “boil” with fish. The first sign that the Georges Bank fish stocks would not last forever was the near disappearance of halibut around 1850 (Bigelow and Schroeder 1953). This, however, did not slow fishermen’s efforts; they merely began to overfish other species such as cod and flounder.

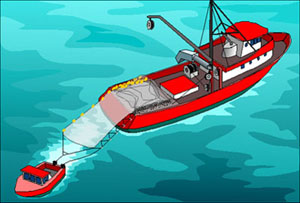

As fishing technology advanced, fishery populations declined. Early fishermen used sail boats or rowboats and single hooked hand lines to catch fish (See Figure 2). But in 1906 the steam trawler was invented, and this forever changed the fishing industry. Trawlers use large nets to catch whole schools of fish at one time (See Figure 3). By 1928 diesel power had been introduced to the fishing community and the industry changed once more by allowing boats to travel further, longer, and faster.

Other advances in the 1920’s included filleting machinery and the invention of frozen foods. Previously fishermen salted fish, limiting its shelf life. Frozen fish sticks opened up a whole new market; because frozen food lasted longer, it could be shipped all over the world. This new technology also changed the fishing vessels. A whole new ship was born: the factory ship (See Figure 4). These huge boats had large nets, filleting machinery, and huge ice boxes, so they were able to catch, fillet, and freeze the fish. This enabled the fishermen to stay longer at sea and catch more fish. Fleets of factory ships from the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Spain, Japan, Canada, the United States, and others decimated fish stocks. “In an hour, a factory ship could haul in as much cod−around a hundred tons−as a typical 17th century boat could catch in a season” (AMNH 1998).

After World War II, the fishing strategy was again revolutionized. The war had established new technology in the fields of aviation and sonar, and fishermen took advantage of these new tools. Planes and boats paired up to find large schools of fish. Fishermen began using sonar as fish-finder, bouncing beams off the ocean floor in order to detect if anything was swimming below the vessel. Luck had been taken out of the fishing game.

Figure 2. Handlining (AMNH 1998) Figure 3. Trawl (NOAA n.d.) Figure 4. Factory ship (NOVA 2005)

Fishing had become too efficient, and as the catch got smaller, the signs of depleting fish stocks grew. In an effort to save the juvenile fish, and there by save generations, a minimum mesh size became mandatory for fishing vessels. These regulations, implemented in 1953, were the first fishing regulations put into affect (NOAA n.d.).

Although steps had been taken to protect the fish, the intense fishing pressure of the world fleets decimated the fisheries, and as the fish continued to disappear, the U.S. government realized that they had to preserve their fishery for themselves. To eliminate foreign competition, the U.S. passed the Magnuson Act of 1976 which established American jurisdiction over the waters up to 200 miles from the shoreline, this area becoming known as the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). (In 1984 the northeastern corner of the Georges Bank was granted to Canada because it lies within 200 miles of Nova Scotia.) The following year in 1977, the New England Fishery Management Council wrote out its first plan for cod, haddock, and yellowtail flounder, already decimated by overfishing. The plan established annual quotas and limited catch per trip, minimum fish size, and larger mesh size for nets. Many fish stocks rebounded slightly after this, so in 1982 quotas and trip limits were abandoned and the domestic fishing fleet grew, assisted by tax incentives and federal subsidies (Dorsey 2004).

Unlimited fishing continued on the Georges Bank, despite the steady decline in catch, until finally in 1994 Amendment 5 limited the number of permits, increased mesh size by 1/2 inch, and began an effort reduction program that would cut time fishing for groundfish by 50% over five years (Dorsey 2004). But it was already too late for the Canadian cod fishery, a moratorium was declared on northern cod fishing. This prompted the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service to conduct an assessment of the cod stock on Georges Bank. Their findings stated "a drastic forty per cent decline over four years, and concluded that the fishing fleet was about twice the size that Georges Bank could sustain." On December 7th, 1994, 9,600 square kilometers of Georges Bank fishing ground was officially closed on an emergency basis, and has remained closed to groundfishing indefinitely (AMNH 1998).

Pressure from the scientific community led the U.S. Congress to sign into law the Sustainable Fisheries Act on October 11, 1996 (NOAA n.d.) which required long-term sustainability management and addressed concerns regarding habitat and by-catch. This was supposed to be a cure-all, but in March of 1997 stocks were reevaluated and although researchers found an increase in some fish numbers, the commercial species were still being overfished. It was the same story in January 1999, when scientists from the National Marine Fisheries Service in Woods Hole, Massachusetts reported that cod white hake, American plaice, and yellowtail flounder along with other species remain overfished. (NFSC 1999).

Government regulations have been lax and have not allowed the fish to recover from decades of overfishing. The New England Fishery Management Council implemented targets for groundfish catch numbers, but these targets were never policed. “In the 1996 fishing year, for example, the fleet caught nearly four times the amount of Georges Bank cod it was supposed to. In 2001, they were still catching more than twice the target" (Cook and Daley 2003). More recently, in August 2005 the National Marine Fisheries Service released a report on the status of groundfish stocks on Georges Bank. “The report showed the results of management efforts from 2001 to 2004. The report found that cod stocks on Georges Bank had dropped 22.6%, despite efforts to stop overfishing. The report also issued a mandate for the council to adopt more restrictive measures to prevent overfishing” (Lovewell 2005).

In 2004 an amendment was made to the Magnuson Act. Amendment 13 implemented quotas and limited days at sea, but will this be enough to save the Georges Bank fisheries? Most scientists ask for a temporary hold on all groundfishing to allow the fishery to recuperate, but some suggest that it will still take decades to regain healthy stocks. The fishing industry is already failing; can the fishing industry and infrastructure survive further cutbacks? Commercial fishing is a part of New England culture and it will be unfortunate to see that element of our background disappear.

Georges Bank is home to many

commercially valuable fish including cod, haddock, herring, flounder, lobster,

scallops, and clam. It is home to more than 100 species of fish, as well

as marine birds, whales, dolphins, and porpoises.

Phytoplankton

The health of marine animals relies greatly on the abundance of Phytoplankton. Phytoplankton are the photosynthetic primary producers of the marine realm. All other marine life is essentially dependent on it. In order to have productive phytoplankton blooms, there must be two basic ingredients: sunlight and nutrients, mainly nitrates and phosphates. The Georges Bank provides such suitable habitat that phytoplankton grow three times faster here than on any other continental shelf (ANMH 1998). Because it is a large shallow area, sunlight easily penetrates the water. It also causes incoming waves to steepen, pulling the deep water to the surface. This recycling of the water delivers the biolimiting nutrients to the phytoplankton. This process is aided by the merging of the Labrador Current flowing south past the bank and the Gulf Stream coming north. The phytoplankton also grows fast on the Georges Bank out of necessity. In the northern regions, where sunlight is limited by the seasons, phytoplankton must "make hay while the sun shines."

Atlantic herring

|

Atlantic herring are small fish, growing only to 18", that are found throughout the Atlantic Ocean. Similar species can be found world-wide and the term "herring" is often used to describe many of these small, schooling fish. The Atlantic herring have a rich history in the northeast. Native Americans would catch them in a going tide using fish weirs (See Figure 5). A far cry from the spotter planes, diesel engines, and purse seines now used to capture entire schools of fish. |

Figure 5. Native weir style (Watershed Watch 2006) |

The purse seine is most commonly used to catch herring, although mid-water trawls and traditional fish weirs are still put into practice. A purse seiner is able to drop a boat off its stern, which will then encircle the school. The net is then cinched, like a draw string, to compact the fish so that a pump can literally vacuum them aboard (See Figure 6). The efficiency of these new technologies implemented after WWII led to a profitable "sardine" canning industry. Canneries once existed up and down the New England coastline, but the industry crashed. After years of foreign and domestic fishing overfishing, the Georges Bank Atlantic herring fishery collapsed in 1977. Landings bottomed out at 2,000 mt following a record breaking year in 1968 with 470,000 mt (See Figure 7). The herring fishery collapsed only one year after the Magnuson Act banned foreign fishing on the Georges Bank.

Figure 6. Purse seining herring (GMA

2006)

|

|

Since that low, the herring fishery has rebounded well and make up the majority of the lobster bait industry. Herring fishing is still allowed on the Georges Bank, but the fishermen must be careful not to exceed by-catch limits for the still recovering goundfish. NOAA Fisheries Service announced on August 25th, 2005 that "the Atlantic herring fishery can proceed on Georges Bank while retaining small amounts of haddock. If reported haddock by-catch in the fishery exceeds that limit, the Georges Bank herring fishery will close, and the zero haddock possession limit for herring vessels will be reinstated (NMFS 2005). |

| Atlantic Cod Legend has it that Atlantic cod were once so abundant on the Georges Bank that men could scoop them from the sea with baskets (CLF 2006). Now they can scarcely be found. On a ten day trip May-April of 2005, the Albatross IV a NOAA research vessel, traversed the bank in 72 tows, and saw few cod. (Lovewell 2005) |

|

|

|

In 1966, at the height of the world fishing fleets, the Georges Bank fishery was producing around 53,134 mt of cod. But the fish stocks could not withstand such intense fishing pressure, and from this peak began a steady decline. Notice in Figure 8 that before 1976 the world catch is far more than the U.S. and Canadian catch, but after the Magnuson Act banned foreign fishing fleets, world catch is the U.S. and Canadian catch combined. |

Also notice in Figure 8 that world catch actually increased U.S. catch more than doubled to fill the gap left by the foreign fleets. Continued pressure again led to a population crash. This last crash prompted more stringent measures and on December 7th, 1994, 9,600 square kilometers of Georges Bank fishing ground was officially closed on an emergency basis, and has remained closed to groundfishing indefinitely (AMNH 1998).

Haddock

Historically, haddock was abundant throughout the Gulf of Maine, with the Georges Bank being one of the most productive haddock grounds in the world (Diddati, 2003). Fleets from all over the world were experiencing record catches in the 1960's, but within that same decade, the fishery collapsed (See Figure 9). The catch biomass dropped from more than 150,000 mt in 1965 to less than 5,000 mt, where it remained throughout most of the 1970s. This historical crash was an integral part in the passage of the Magnuson Act which ended foreign fishing in 1976. Landings began to increase again in 1977 through 1980, reaching 27,500 mt, but subsequently declined to 2,300 mt in 1995 (Brown 2000).

|

|

After dipping to a record low in the 1990's, Georges Bank haddock has seen rapid rebuilding over the past decade. (NMFS 2005). By 1996, Georges Bank haddock was reported to have doubled its biomass from record low levels in 1993 (Dorsey 2004) and recent reports show promising signs. On its trip the Albatross IV |

examined hundreds of pound of juvenile haddock,

though found few cod. (Lovewell

2006). The haddock fishery is doing so well, that like

the scallopers, fishermen are pressuring for the reopening of Georges Bank.

Although opening the fishery would greatly help the struggling fishermen, it is

important that we properly manage the fishery as it is the most

productive spawning area for haddock in the northwest Atlantic (Diddati

2003).

.

Atlantic Sea Scallops

The Georges Bank has historically been one of the two prime Atlantic scallop fishing grounds, the other found in the Mid-Atlantic. Initial regulations in the 1980's and early 1990's attempted to manage the fishery, implementing a shell height of 3.5 inches with a 10% tolerance (meaning 10% of the catch was allowed to be under this limit (Kirkley and DuPaul 1998). However, greatly reduced landings in the 1990's showed signs of a dying population. After an evaluation of the fishery, further restrictions on scallops were instituted with the passage of Amendment 4 in 1994 (Kirkley and DuPaul 1998). These included crew limits, scallop size limits, and limited area and days of fishing on Georges Bank (MFM 2001).

|

|

About half of the Georges Bank was closed to scallop fishing in 1994, but after stocks continued to decline, the Georges Bank was closed completely to scallop fishing by the passage of the Sustainable Fisheries Act in 1996 (MFM 2001). In Figure 10 the population boom associated with this complete closure is appartent.This moratorium only lasted three years. In 1999, pressure from the fishing community led to limited scalloping on a portion of Georges Bank's Closed Area II. Since the reopening, higher catch results than have been seen in 40 years have been reported (MFM 2001). |

The biggest concern in scallop fishing is not necessarily overfishing, as the scallop has a short life span and females are highly fecund, producing millions of eggs (NEFMC 2002), but the dredging gear used by scallop fishermen. The dredge is a mesh bag made of metal rings attached to a steel frame. To harvest scallops, this heavy dredge is dragged across the ocean floor; chains hanging from the frame sweep scallops into the bag (See Figure 11.) Dredging causes two ecological problems.

|

First, the heavy gear scrapes along the bottom and flattens the natural topography, homogenizing the seafloor and destroying habitat for many marine creatures. Second, a high amount of bycatch is associated with this style of fishing. Because of recent concerns regarding dredges, sweep chains have been lightened to mitigate bottom damage, escape routes for fish have been enlarged, and scallopers allow nets to lay fallow for several minutes at the end of a tow in order to facilitate escape by ground-fish. (MFM 2001) Protection for the endangered Loggerhead Sea turtles may soon follow. |

|

On May 27th,2005 the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) proposed a rule requiring scallop dredge vessels in fishing in the mid-Atlantic to modify dredges with chain mat configuration to help reduce turtle by-catch in the May through November months (Frady 2005). Another thing to look forward to is the possibility of a new "lightweight" dredge. MIT in conjunction with Sea Grant is developing a scallop dredge design that uses hydronamic forces rather than weight to keep the gear on the bottom. (MFM 2001).

Georges Bank has set an example of how well stocks can rebound if they are given the opportunity and has given scientists a reference point to study what happens in the marine realm without human disturbance. Some species like scallops have rebounded so quickly that they have reached levels healthy enough to harvest, while others like the cod are having a more difficult recovery. Cod may face even more difficulty as global warming changes the Georges Bank, because the Atlantic cod is a cold water fish. Global warming may present an array of new challenges to the Georges Bank.

Over the past three years, the water temperature on Georges Bank has been three degrees above average (Lovewell 2005). Future global warming may change the Georges Bank and its wildlife as drastically as previous global temperature changes have done. With continued glacial melt, the water over the bank will become deeper, and this will affect the productivity of phytoplankton and other seaweeds. Global warming may also result in warmer waters which could mean an increase in invasive species on the Georges Bank. One such species, the sea squirt, was discovered on the Georges Bank in 2003 (Valentine 2005). These tunicates form large mat-like colonies that choke out the sea floor habitat. The species thrives in marine environments that lie within its preferred temperature range of 28-750 F (Mecray and Frady 2005). Climate change could potentially favor invasive non-native species by either creating more favorable environmental conditions for them or by stressing native species to the point of being unable to compete against new rivals. Invasive species can be harmful to native marine life for reasons including competition for food, interbreeding and variations of native gene pools, changing predator/prey relationships, and potential for spreading of new diseases.

Just as diseases such as malaria are moving north on the continents, disease trends are migrating in the oceans. Georges Bank shellfish, primarily lobster and crab species, have recently been suffering from shell disease. Although not much is known about this fairly new disease, scientists believe it is closely linked to climate change and pollution. Scientists all over the world are concerned of this relationship. “Emergence of new diseases is being helped by a long-term warming trend. Scientists believe that marine life is at growing risk from a range of diseases whose spread is being hastened by global warming and pollution” (Kirby 1999).

It is still unclear exactly what is in store for the Georges Banks, but hopefully more research on topics such as sediment type, topography, current strength, water chemistry, habitat disturbance, and species distribution will help us better understand our marine ecosystems and help manage them properly for long term sustainability.

|

|

The U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy, a council mandated to conduct a comprehensive review of national ocean policy, released its final report in 2004. It highlighted the importance of sound management of our oceans' resources. In response to this evaluation, President George W. Bush announced his Ocean Action Plan. This plan is focused on making our oceans, coasts, and Great Lakes cleaner, healthier, and more productive.

|

Enhancing Ocean Leadership and Coordination

Advancing our Understanding of Oceans, Coasts, and Great Lakes

Enhancing the Use and Conservation of our Ocean, Coastal and Great Lakes Resources

Managing Coasts and Their Watersheds

Supporting Maritime Transportation

Advancing International Ocean Science and Policy

|

Included in this Ocean Action Plan is President Bush's solution for "Enhancing the Use and Conservation of our Ocean Resources." Bush's plan for executing this is to "Promote Greater Use of Market-based System for Fisheries Management." This approach to management will adopt an individual fishing quota (IFQ) system. IFQ systems offer a market-based approach that moves fisheries management away from "more cumbersome" and "inefficient" regulatory policies (Dept. of Commerce 2006). This new approach to management worries me. I believe we should be approaching fishery management with an ecological mind frame, not with a market-based system. The ocean is a dynamic ecosystem where each piece affects the whole. When managing ecosystems, single-species regulations have proven ineffective. We must begin to regard the ocean as its own living organism and regulate it appropriately so that all species are considered as integral pieces of this whole. Fisheries management must move beyond a single-species approach to one that includes consideration of marine ecosystems, where the importance of habitat and trophic relationships are directly incorporated into the setting of fishing regulations. "Natural systems are wholes whose specific structures arise from the interactions and interdependence of their parts. Systemic properties are destroyed when a system is dissected, either physically or theoretically, into isolated elements. Although we can discern individual parts in any system, the nature of the whole is always different from the mere sum of its parts" (Capra 1982).

|

If you would like the Bush Administration to consider ecological management practices rather than market-based systems, please send this form letter. |

Earlier this year, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez proposed further restriction on the Georges Bank fishery including limited days at sea. Although any act towards preservation of our oceans' resources is greatly appreciated, it causes further stress on the fishing community. Many fishermen are already struggling to get by and further restrictions may put them out of business completely.

Amaral, Kimberly, 2 March 1999.

Georges Bank: A

Brief History of the Past 26,000 Years. Retrieved on 24 April 2006 from

http://globec.whoi.edu/globec-dir/GeorgesHistory1.html.

American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), 1998.

How Gear and Greed Emptied

the Georges Bank. Retrieved on 26 March

2006 from

http://sciencebulletins.amnh.org/biobulletin/biobulletin/story1208.html.

and

Fishes of the

Gulf of Maine. Retrieved on 24 April 2006 from

http://www.gma.org/fogm/Hippoglossus_hippoglossus.htm

Brodziak, Jon and Traver, Michele and Col, Laurel, 2005.

Georges Bank Haddock. Retrieved on 14

February 2006 from

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/nefsc/publications/crd/crd0513/garm2005b.pdf.

Brown, Russell, January 2000.Haddock.NEFCS.

Retrieved on 3 May 2006 from

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/sos/spsyn/pg/haddock/#gbland.

Capra, Fritof, The Turning Point: Science, Society, and the Rising Culture. Bantam Books, New York, 1982.

Conservation Law Foundation (CLF), 2006.

Deep Sea

Rescue: Is Time Running Out for Georges Bank Cod? National Resource

Defense Council. Retrieved on 29 April 2006 from

http://www.clf.org/uploadedFiles/CLF/Programs/Healthy_Oceans/

Fishing_Communities/Protecting_Groundfish/gfish_Factsheet_GBCod.pdf.

Conservation Law Foundation (CLF), 2004.

Map of Georges Bank. Retrieved on 10

April 2006 from

http://www.clf.org/programs/cases.asp?id=809.

Cook, Gareth and Daley, Beth. 26 October 2003.

A Once Great Industry on the Brink.

Boston Globe. Retrieved on 26 March 2006

from http://www.boston.com/news/local/maine/articles/2003/10/26/a_once_great_industry_on_the_brink/.

Diddati, Paul, 9 July 2003.

Species Profiles>Haddock.

Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. Retrieved on 3 May 2006 from

http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dmf/recreationalfishing/haddock.htm.

Department of

Commerce, 2006. Management and Budget. Retrieved on 3 May 2006 from

http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2006/commerce.html.

Dorsey, Eleanor, 2004.

The Road to Groundfish Collapse and Turning The Corner to Recovery.

Conservation Law Foundation.

Retrieved on 2 March 2006 from

http://www.clf.org/programs/cases.asp?id=406.

Frady, Teri, 27 May 2005.

Sea Scallop Gear Change Proposed to Protect Sea Turtles.NOAA.

Retrieved on 3 May 2006 from

http://www.publicaffairs.noaa.gov/releases2005/may05/noaa05-r114.html.

Kirby, Alex, 2 Sept. 1999.

Marine Diseases Set to Increase.

BBC News. Retrieved on 26 March 2006 from

http://newswww.bbc.net.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/436702.stm.

Kirkley, James and William DuPaul, December 1998.

The U.S. Northwest

Atlantic Sea Scallop Fishery. Virginia Institute of Marine

Science. Retrieved on 2 March 2006 from

http://www.fishingnj.org/artscallop.htm.

Lovewell, Mark Alan, 2006.

Cod in State of Collapse. Vineyard Gazette. Retrieved on 29 April

2006 from

http://www.mvgazette.com/features/fishing/georges_bank/?document=georges_cod_collapse.

Lovewell, Mark Allen, 2005.

Council on

Fisheries Struggles to Reach Common Ground. Vineyard Gazette.

Retrieved on 26 March

2006 from

http://www.mvgazette.com/features/fishing/fishermen/fisheries_council.php.

Mayo, Ralph and O'Brien, Lorrtea, 2000.

Atlantic Cod. Retrieved on 2 February 2006 from

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/sos/spsyn/pg/cod/.

Mecray, Ellen and Teri Frady, January 2003. Invasive Sea Squirt

Alive and Well on Georges Bank. USGS. Retrieved on 3 March

2006 from

http://soundwaves.usgs.gov/2005/01/fieldwork4.html.

Monterey Fish Market (MFM), 2001.

Scallops and Sustainability.

Webseafood. Retrieved on 2 March 2006 from

http://www.webseafood.com/sustainability/scallops.htm.

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), 8 June 2005.

Atlantic Herring Fishery on Georges Bank Gets Haddock Limit.

NOAA.

Retrieved on 3 May 2006 from

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/press_release/2005/nr0508.htm.

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS),

7 February 2006. Small Entity Compliance Guide. NOAA.

Retrieved on 3 May 2006

from

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/press_release/.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA),

n.d. Brief History of

Groundfishing. Retrieved on 24 April 2006 from

http://www.noaa.gov/nmfs/groundfish/grndfsh1.html.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA),

n.d. Sustainable Fisheries Act.

Retrieved on 24 April 2006 from

http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/sfa/.

National Park Service (NPS), 1 April 2005.

Geology of Cape Cod National

Seashore. Retrieved on 24 April 2006 from

http://www2.nature.nps.gov/geology/parks/caco/.

New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC), 2002.

Sea Scallop Fishery Management

Plan. Retrieved on 2 March 2006

from

http://www.nefmc.org/scallops/summary/scallop.pdf.

Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC), 27 January

1999.

Scientific Analyses Confirm Need to Improve Protection of Five

Stocks from Overharvesting. Retrieved on 24 April 2006 from

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/press_release/1999/news99.02.html.

NOVA Fisheries, 2005. Frozen at Sea. Retrieved on 2 March 2006 from http://www.novafish.com/pages/ships.html.

O'Brien, L., 2000. Georges

Bank Atlantic Cod. Retrieved on 15 February 2006 from

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/nefsc/publications/crd/crd0120/0120-2a.pdf.

Sea Grant University of Delaware, 2006. Scallop. Retrieved on 8 March 2006 from

http://www.ocean.udel.edu/mas/seafood/scallops.html.

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), 13 October

2005. Ocean Invaders in Deep Time.

Retrieved on 26 March 2006 from

http://news.mongabay.com/2005/1013-invasive.html.

Smolowitz, Robert, 1999.

Bottom Tending Gear Used in

New England. Effects of Fishing Gear on the Sea Floor of New England.

Retrieved on 2 March 2006 from

http://www.fishingnj.org/artsmolowitz.htm.

Valentine,

Dr. Page, November 2005. Sea Squirt Colonies Persist on Georges Bank.

USGS. Retrieved on 3 May 2006 from

http://soundwaves.usgs.gov/2005/11/fieldwork2.html.

Valentine, Dr. Page, 11

December 2003.

Geology and the Fishery of Georges Bank. United States Geological

Survey. Retrieved on

24 April 2006 from

http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/georges-bank/.

Watershed Watch, 2006.

Nlaka'pamux Fish Weir. Retrieved

on 2 May 2006 from

http://www.watershed-watch.org/ww/Photos/nlakaweir.html.

.